The war in Somalia took the lives of her father and her sister. Nevertheless, Ilwad Elman found the strength, together with her mother, to develop Elman Peace, an organisation that works to build peace in Somalia and beyond. “We are continuing the work to honour them. It’s healing for us, to live a life in service.” Elman Peace has been awarded the KBF Africa Prize for these achievements.

Working amid the civil war in Somalia in recent decades, Elman Peace has been forced to evolve constantly. Their mission has remained unchanged: to build peace in a conflict-scarred nation. They understand that this demands far-reaching change, long after the parties to the conflict have laid down their arms.

“Peace means so much more than the guns falling silent”, says Ilwad Elman, who leads the NGO alongside her mother, executive director Fartuun Adan. “There are so many other elements that create an environment that enables peace and allows it to flourish, in individuals and also in society.”

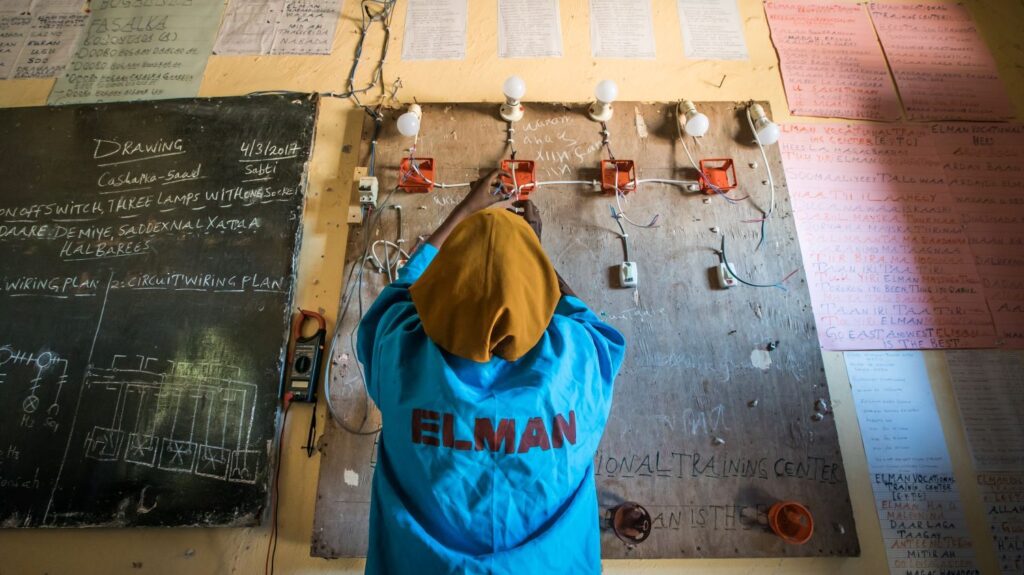

Their holistic, community-focused approach – which includes education, training, psychosocial support, empowerment, collaboration and monitoring – has earned them praise far and wide. Their achievements now include the biennial KBF Africa Prize. Elman Peace has been recognised for its fight for social justice and human rights through promoting peace, cultivating leadership and empowering people who are marginalised in society, especially young people and women.

The family that founded Elman Peace has not been spared the experience of war and violence that have afflicted the people of Somalia. As a child, Ilwad went abroad with her mother and two sisters to seek refuge from the civil war. Their father Elman Ali Ahmed stayed on to rescue youngsters from the grasp of rival warlords who wanted to press them into service as fighters, with his project Drop the Gun, Pick up the Pen. In 1996 Elman was murdered by some of those angered by his campaign.

Ten years later his wife returned from Canada to continue her husband’s work. In 2010, at only 20 years of age, their daughter Ilwad was also drawn to return to Somalia and join the organisation. Her sisters followed her example. In 2019 the family suffered violence again: the oldest daughter Almaas was shot dead in the airport compound in the Somali capital Mogadishu.

Thirty years later, Elman Ali Ahmed’s legacy lives on. Drop the Gun is still running; the programme has reintegrated thousands of young people into their communities. This year, Almaas’s memory was honoured with the opening of a girls’ leadership academy in her name, offering four-year courses for 200 girls from disadvantaged backgrounds.

“We have shown the world the scale of suffering in Somalia,” Ilwad Elman says. “It’s not enough for us to just document this; we have to respond as well.” The response has been impressive. The organisation has a huge number of projects focused on defending human rights and offering opportunities to give overlooked Somalis, especially women and young people, a greater role in constructing their nation’s future.

Sister Somalia, for example, is the country’s first crisis centre – which has now become a whole network – helping those who have suffered sexual and gender-related violence. Equal Voices equips women and youth leaders with the tools they need to participate meaningfully in political processes. Elman Peace builds alliances, shares information and good practices and runs national, African and global campaigns to bring about change.

Ilwad Elman divides her time between working in the field on the activities of Elman Peace Centres – in the Mogadishu headquarters, it runs eight regional centres – or out speaking to local communities involved in their Peace by Africa initiative, and addressing world leaders at the UN and other forums.

Elman Peace has now expanded its advocacy work into the arena of climate change, which is exacerbating insecurity in Somalia on a massive scale. When extreme weather and recurrent droughts cause extreme vulnerability in certain areas, armed groups exploit the situation to attract new recruits. “We are at the front line of the clash between the climate and security. Environmental issues are fuelling conflicts. “When people can no longer care for themselves and lose their dignity, they are capable of doing anything to survive. Terrorist organisations thrive in that context.”

Her enthusiasm for this issue is matched by her passion for promoting personal well-being, pioneering approaches that are unfamiliar in Somalia. “We are noticing how programmes like ocean therapy also benefit our staff,” she says. Local human rights activists sometimes suffer from secondary trauma through their work and, like all Somalis, they may also be directly affected by violence. “In Somalia, speaking to a professional – a stranger – about what you have experienced is a very foreign approach. It may be viewed as weakness, or you could even seem ungrateful since, after all, you are lucky to have survived.”

Elman Peace now aims to spend some of the prize money on developing services for front line workers. “Every year we lose people that have done so much work in this space, because they cannot handle it anymore,” Ilwad Elman says. “Peacebuilding activists are supposed to be the pillars of strength in the community, but we also have our share of trauma, hardships, and loss. Unlike most international NGO workers, we don’t get any respite.”

She did consider leaving Somalia herself, after her sister was killed: “That was the first time I ever felt disillusioned,” she says. Instead, she has returned with renewed commitment: “There is no plan B. How else can we justify all of this loss? We have to continue the work to honour them. It’s healing for us, to continue to live a life in service.”

To stay informed about news from our partners and new calls for proposals

Subscribe to the newsletter